I worried so much about prescription writing in my 3rd year of medical school. I probably killed a whole tree tearing up prescriptions that were wrong.

Why did I worry so much about it? Prescription writing was not covered very well at my medical school. And with the amount of material that needs to be covered in those 4 years, I wouldn’t be surprised if prescription writing isn’t covered very well at any medical school.

How to Write a Prescription in 4 Parts

- Patient’s name and another identifier, usually date of birth.

- Medication and strength, amount to be taken, route by which it is to be taken, and frequency.

- Amount to be given at the pharmacy and number of refills.

- Signature and physician identifiers like NPI or DEA numbers.

That is the basic outline of how to write a prescription. We’ll be going into the details of each step below. But first, let’s look at why it’s so important to get this skill right.

The Cost of Poor Prescription Writing

Poorly written prescriptions may be one of the main reasons there are so many medication errors today. Look at some of these commonly quoted statistics:

- Medication errors occur in approximately 1 in every 5 doses given in hospitals.

- One error occurs per patient per day.

- Approximately 1.3 million injuries and 7,000 deaths occur each year in the U.S. from medication-related errors.

- Drug-related morbidity and mortality are estimated to cost $177 billion in the U.S.

While these are just estimates from various studies and statistical models, the numbers are staggering. If there are 800,000 physicians in the United States, each physician accounts for $221,250! Do you still wonder why malpractice insurance is so expensive?

Approximately 1.3 million injuries and 7,000 deaths occur each year in the U.S. from medication-related errors.Click To TweetHopefully, if you are reading this, you’re interested in not making mistakes. Even though I don’t think I caused any major harm to any of my patients with prescription errors, I wish I had read something like this when I first started writing prescriptions in my 3rd year of medical school.

How to Write Prescriptions

A prescription is an order that is written by you, the physician (or future physician), to tell the pharmacist what medication you want your patient to take. In this post, I’m going to break down all the different parts of a prescription, how to write each section, and what to look out for. Watch the video above if that’s a more appealing format to you!

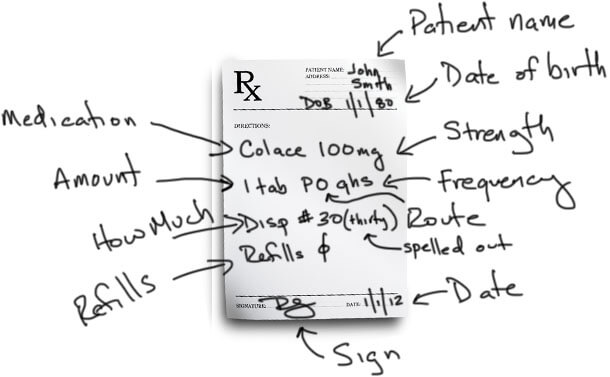

Breaking Down the Prescription Format

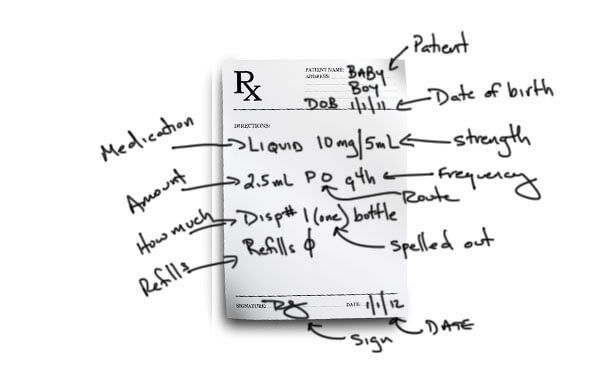

As I hinted above, here is the basic format of a prescription: First, we have the patient’s name and another patient identifier, usually the date of birth. Then we have the medication and strength, the amount to be taken, the route by which it is to be taken, and the frequency. For “as needed” medications, there is a symptom included for when it is to be taken.

The prescriber also writes how much should be given at the pharmacy and how many refills the patient can come back for. The prescription is completed with a signature and any other physician identifiers like NPI number or DEA number. Then the prescription is taken to the pharmacist who interprets what is written and prepares the medication for the patient. Now let’s look at each part of this individually.

Patient Identifiers

According to the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) national patient safety goals, at least two patient identifiers should be used in various clinical situations. While prescription writing is not specifically listed as one of these clinical situations, medication administration is. I think prescription writing should be in this category as well.

Two patient identifiers should be included in a prescription to avoid medication errors.Click To TweetThe two most common patient identifiers are their full name and date of birth. Patient identifiers are the first things to write on a prescription. This way you don’t write a signed prescription without a patient name on it that accidentally falls out of your white coat and onto the floor in the cafeteria.

Drug/Medication

This is an easy one. This is the medication you want to prescribe. It generally does not matter if you write the generic or the brand name here unless you specifically want to prescribe the brand name.

If you do want to prescribe the brand name only, you specifically need to indicate, “no generics.” There are several reasons you might want to do this, but we won’t get into that here. On the prescription pad, there is a small box which can be checked to indicate “brand name only” or “no generics.”

If you only want to prescribe the brand name of a drug, you need to indicate 'no generics' on the prescription.Click To TweetStrength

After you write the medication name, you need to tell the pharmacist the desired strength. Many, if not most, medications come in multiple strengths. You need to write which one you want.

Often times, the exact strength you want is not available, so the pharmacist will substitute an appropriate alternative for you. For example, if you write prednisone (a corticosteroid) 50 mg, and the pharmacy only carries 10 mg tablets, the pharmacist will dispense the 10 mg tabs and adjust the amount the patient should take by a multiple of 5.

Amount

Using my previous example for prednisone, the original prescription was for 50 mg tabs. So you would have written, “prednisone 50 mg, one tab….” (I’ll leave out the rest until we get there). The “one tab” is the amount of the specific medication and strength to take.

Again using my previous example, due to the 50 mg tabs not being available, the instructions would be rewritten by the pharmacist as “prednisone 10 mg, five tabs….” You can see that “one tab” is now “five.” Pharmacists make these changes all the time, often without any input from the physician.

Route

Up until this point, we have been using plain English for the prescriptions. The route is the first opportunity we have to start using English or Latin abbreviations. Note: It is often suggested that to help reduce the number of medication errors, prescription writing should be 100% English, with no Latin abbreviations. I will show you both and let you decide.

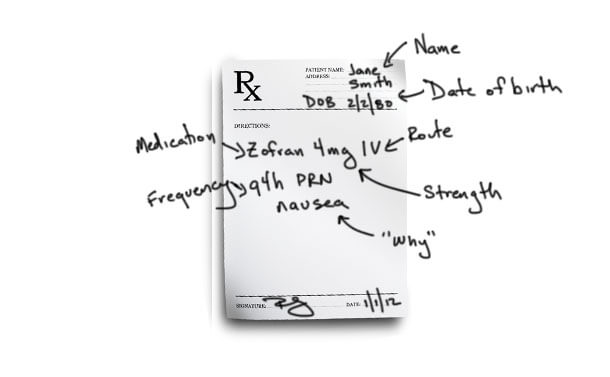

There are several routes by which a medication can be taken. Some common ones are by Mouth (PO), per rectum (PR), sublingually (SL), intramuscularly (IM), intravenously (IV), and subcutaneously (SQ).

It is often suggested that to help reduce the number of medication errors, prescription writing should be 100% English, with no Latin abbreviations.Click To TweetAs you can see, the abbreviations are either from Latin roots like PO (“per os”) or just common combination of letters from the English word. Unfortunately, when you are in a hurry and scribbling these prescriptions, many of these abbreviations can look similar. For example, intranasal is often abbreviated “IN,” which, if you write sloppily, can be mistaken for “IM” or “IV.”

Common route abbreviations for prescription writing:

- PO (by mouth)

- PR (per rectum)

- IM (intramuscular)

- IV (intravenous)

- ID (intradermal)

- IN (intranasal)

- TP (topical)

- SL (sublingual)

- BUCC (buccal)

- IP (intraperitoneal)

Frequency

The frequency is simply how often you want the patient to take the medication. This can be anywhere from once a day, once a night, twice a day, or even once every other week. Many frequencies start with the letter “q.” This Q is from the Latin word quaque, which means once.

So in the past, if you wanted a medication to be taken once daily, you would write QD, for “once daily” (“d” is from “die,” the Latin word for day). However, to help reduce medication errors, QD and QOD (every other day) are on the JCAHO “do not use” list. So you need to write out “daily” or “every other day.”

Common frequencies abbreviations for prescription writing:

- daily (no abbreviation)

- every other day (no abbreviation)

- BID/b.i.d. (twice a day)

- TID/t.id. (three times a day)

- QID/q.i.d. (four times a day)

- QHS (every bedtime)

- Q4h (every 4 hours)

- Q4-6h (every 4 to 6 hours)

- QWK (every week)

The “Why” Portion

Many prescriptions that you write will be for “as needed” medications. This is known as “PRN,” from the Latin pro re nata, meaning “as circumstances may require.” For example, you may write for ibuprofen every 4 hours “as needed.”

What physicians and medical students commonly miss with PRN medications is the “reason.” Why would it be needed? You need to add this to the prescription. You should write “PRN headache” or “PRN pain,” so the patient knows when to take it.

How Much

The “how much” instruction tells the pharmacist how many pills should be dispensed, or how many bottles, or how many inhalers. Typically, you write the number after “Disp #.”

I highly recommend that you spell out the number after the # sign, even though this is not required. For example, I would write “Disp #30 (thirty).” This prevents someone from tampering with the prescription and adding an extra 0 after 30, turning 30 into 300.

Refills

The last instruction on the prescription informs the pharmacist how many times the patient can use the same exact prescription, i.e. how many refills they can get.

For example, let’s take refills for oral contraceptives for women. A physician may prescribe 1 pack of an oral contraceptive with 11 refills, which would last the patient a full year. This is convenient for both the patient and physician for any medications that will be used long term.

Prescription Writing Examples

To finish up, here is a list of the JCAHO “Do Not Use” List:

- U or u (unit) – use “unit”

- IU (International unit) – use “International Unit”

- Q.D./QD/q.d./qd – use “daily”

- Q.O.D./QOD/q.o.d./qod – use “every other day”

- Trailing zeros (#.0 mg) – use # mg

- Lack of leading zero (.#) – use 0.# mg

- MS – use “morphine sulfate” or “magnesium sulfate”

- MS04 and MgSO4 – use “morphine sulfate” or “magnesium sulfate”

Links and Other Resources

- Check out my Specialty Stories podcast for interviews with doctors practicing in a wide variety of specialties and locations.

- Related episode: Resident Duty Hours and the Ripple Effect.

- Related episode: Dr. Pho of KevinMD Talks About Healthcare Today.

- Check out my Board Rounds podcast for help preparing for the USMLE Step 1 and COMLEX Level 1 exams.